The “Blockbuster Dilemma” in Biotech

We studied ~10 commercial-stage companies and learned about this interesting theme. Amgen, Genentech, Biogen, Regeneron, Vertex, Gilead, Celgene, Abbvie...

Biodraft_ is a biotech blog started by Liang Chang (PhD student at Broad/Harvard) and Kirill Karlin, MD (pathology resident at BIDMC/HMS). As trainees in science/medicine and students in biotech, we post our biotech study notes here, which are mostly deep-dive analyses of interesting biotech areas we recently learned. Click here for an introduction article about Biodraft, Liang, and Kirill.

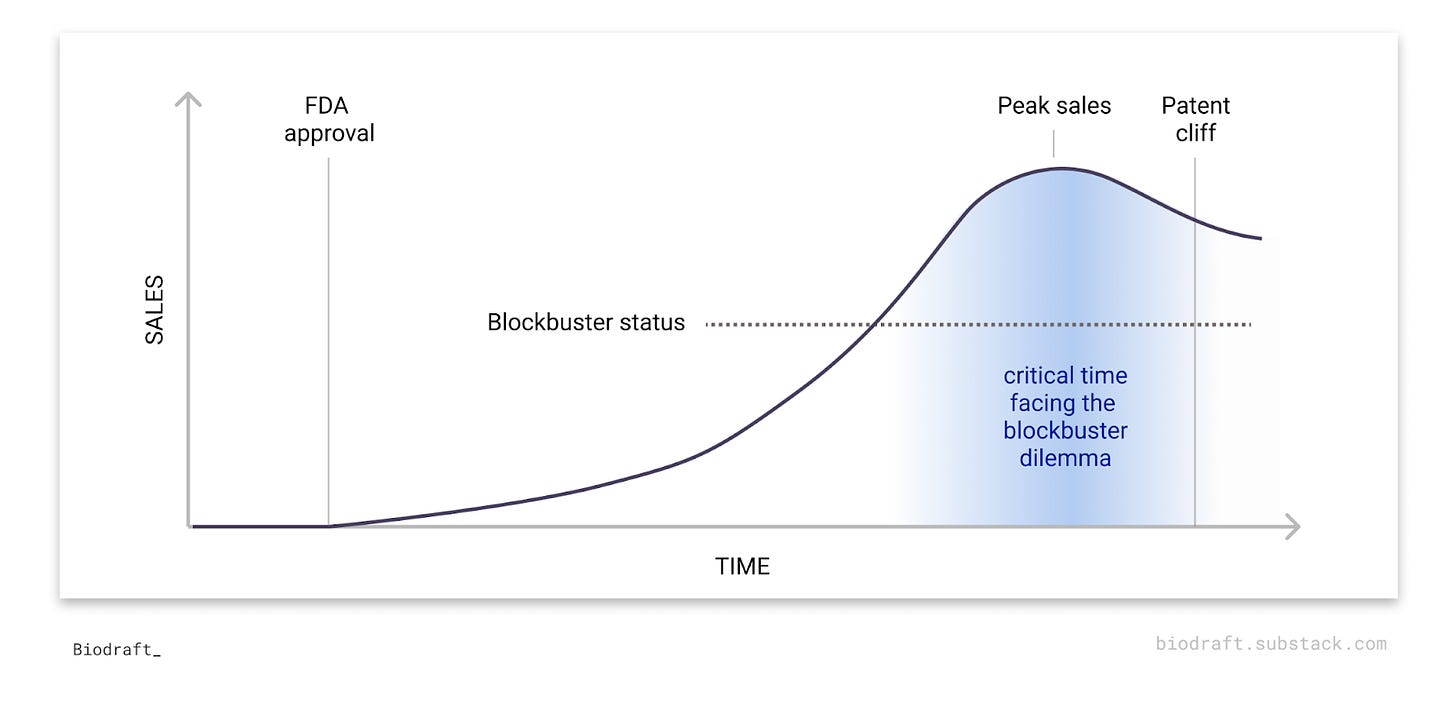

Having a blockbuster drug is both a blessing and a curse for commercial-stage biotech companies.

Intuitively, making a blockbuster drug (annual sale of $1 billion+) is the ultimate dream for every biotech, representing not only business success but also a positive impact on patients' lives. However, after the first blockbuster, the clock starts ticking. The patent cliff is not far away and pressure for the next success is fast approaching. Companies facing a critical time are usually all over the biotech news, juggling between a push for optimizing their own R&D arm or a push for an M&A.

So why is “blockbuster dilemma” a recurring theme for commercial-stage biotech companies? What kind of efforts do companies commonly take to overcome this dilemma? In this deep dive article, we study ~10 biotech companies after their first blockbuster drug to understand this interesting recurring theme in biotech.

What is a blockbuster drug?

Traditionally, a blockbuster drug is defined as a drug with annual sales of $1 billion or more. In 2021, the top 10 best-selling drugs in the world have all achieved more than $7B in annual sales, and drugs on top of this list can hit the $10B or even $20B annual sales mark.

We can see many familiar names on this list: mRNA COVID vaccines that saved the world, anti-PD1 antibodies (Keytruda and Opdivo) that have transformed the standard care of many cancer types, autoimmune drugs (Humira, Stelara, Dupixent) that thousands of patients regularly inject…

But..why do blockbuster drug becomes a curse for biotech?

(1) Patent cliff

After a blockbuster drug hits the market, the multi-billion annual sales rely on one crucial factor: market exclusivity. Under patent protection periods, no other manufacturers are allowed to sell the same blockbuster drug, thus creating a lucrative market monopoly. This incentive system is the foundation for our current biotech ecosystem, since pharma/biotechs are justified to take risky R&D efforts to make new drugs when the payout is somewhat certain if the drug works in the end. However, the market exclusivity period is limited. The patent period is currently 20 years since its first filing in the US. Extracting time spent in discovery, pre-clinical and clinical testing, the median market exclusivity time for a drug is ~12 years.

So what happens after 12 years? Generic or biosimilar drugs can quickly get into the market at a much cheaper price. The Hatch-Waxman Act passed in 1984 encourages generic drugs to get into the market, since generic drug developers just need to file an Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) to FDA to demonstrate that the generic is chemically and biologically equivalent to a previously approved drug, so that they can skip expensive clinical trials. Furthermore, the first generic drug with ANDA approval has 190 days of generic market exclusivity, further encouraging generic players like Teva and Dr. Reddy’s to get into the market at the very first possible moments. Peter Kolchinsky’s blog articles and book explain this “biotech social contract” concept really well. As a result, blockbuster drugs lost market share right after the patent cliff. For example, 2 years after Lipitor’s patent cliff, the annual sale is bare ~20% of its peak sale.

(2) Future revenue matters

Most commercial-stage biotech companies are public companies, and the perceived market value of these companies (as reflected by stock price) is largely determined by their ability to generate profits in the future. For example, discounted cash flow (DCF), a common valuation method of biotech stocks, converts probability-adjusted future drug revenue in the next few years to the value of the stock today. That’s why clinical-stage biotech companies have a billion-dollar worth of valuation with no revenue but just operating costs for now, and why biotech stocks get up after a phase 3 success while still months away from making the first drug sale. A remarkable recent example: Alnylam’s TTR-silencing RNAi candidate met the primary endpoint in a Ph3 trial in ATTR amyloidosis with cardiomyopathy, a big indication with as many as 300,000 global patients, and the stock is up by nearly 50%.

Thus, in order to grow the company to the next level, biotech companies need to find more future revenue streams beyond the initial blockbuster. These biotechs often heavily rely on 1 blockbuster drug to generate current revenue, and the pressure is high if they couldn’t find the next blockbuster in line after the painful patent cliff.

(Another strategy is to distribute current profits to shareholders as dividends. Many pharma companies pay dividends, but it’s uncommon for biotechs. Amgen is one of the dividend-paying exceptions)

How to deal with the blockbuster dilemma?

The goal is simple: either get another blockbuster drug in the future, or make more money out of the existing blockbuster. We identified a few common strategies after looking into ~10 companies:

(1) Pursued R&D internally

This is the dream of every biotech company: to build a robust R&D engine that continuously generates new blockbuster drugs in the future. But it’s much easier said than done. Drug development is risky. The success rate from Phase I to approval over 2011–2020 was less than 10%. Even if a new drug gets to the market, it’s hard to be a blockbuster commercially. There are nearly 7,000 FDA-approved drugs, but less than 100 are blockbusters in 2021.

Happy story: Regeneron. After their first blockbuster Eylea (an anti-VEGF biologics treating Wet Age-Related Macular Degeneration - wAMD) hit the market in 2011 and became one of the historical best-selling drugs in ophthalmology, Regeneron continues to generate new blockbuster biologic drugs before Eylea falls off from the patent cliff. Dupixent, an anti-IL-4R antibody that inhibits the Th2 arm of the adaptive immune system, has scored approval in several indications including asthma and atopic dermatitis, and achieved $6.2B in sales in 2021. REGEN-COV, one of the first COVID-19 neutralizing antibodies, also achieved nearly $6B in sales in 2021.

Sad story: Biogen’s revenue largely depend on Tecfidera (a small molecule drug treating multiple sclerosis with an unspecified mechanism of action) and Spinraza (a gene-splicing-regulating ASO that treats spinal muscular atrophy), but Tedcfidera has already fallen off from the patent cliff and the patent expiration time for Spinraza is 2023. To seek the next blockbuster, Biogen effectively “all in” with neuroscience. They are the firmest believer in the “amyloid hypothesis” of Alzheimer’s disease, and the conditional approval of Aduhelm by FDA last year is one of the most unscientific and controversial decisions ever. But the Aduhelm blockbuster dream didn’t come true: CMS refused to cover this drug, the 2021 sale number is just $3M, and even one of the seminal scientific papers to support the “amyloid hypothesis” had data fraud issues (Derek Lowe has an awesome article on this matter).

(2) Acquire early-stage assets, often through collaboration

Apart from in-house R&D, another popular approach is to get drug candidates through business development. In our previous article on platform biotech companies, we discussed BD/partnership from the “seller’s perspective”. In a nutshell, early-stage biotech companies (“sellers”) can collaborate with larger biotech or pharma companies (“buyers”) through either platform-centric collaborations that are more early-discovery centric around the novel platform technologies, or asset-centric collaborations often take place when the platform company’s lead candidate already achieved preclinical or even clinical proof-of-concept. In the following section, we are going to discuss the “buyer’s perspective”.

Some commercial-stage biotech companies spend more effort on earlier-stage collaborations with small biotechs. Vertex is a great example. Their success story is currently 100% dependent on revenues from the cystic fibrosis franchise (Kalydeco, Orkambi, Symdeko, Trikafta), but 3 out of 4 drugs in this lineup will face patent expiration by 2030. To score the next blockbuster, in addition to their in-house pipeline, they also actively establish early collaborations with younger biotechs mostly on novel technologies. One major area of interest is CRISPR gene editing, as Vertex has established collaborations with CRISPR Therapeutics (one of the initial 3 CRISPR companies), Mammoth Biosciences (smaller Cas enzymes that can be packaged into AAV size limit for in vivo editing), Arbor Biotechnologies (novel nucleases and transposases), Obsidian Therapeutics (small molecule switch for gene editing), and Exonics Therapeutics (using gene editing to treat genetic muscle diseases). In addition, they collaborated and later acquired Semma Therapeutics which uses iPSC-derived pancreas islet cells to treat type 1 diabetes (Here’s a powerful NYT story behind this company and its famous co-founder Doug Melton).

(3) Acquire later-stage assets, often through M&A

Some other “buyer” companies prefer to acquire later-stage drug candidates. These assets, often in later-stage clinical development, are less risky in nature and have a higher chance to generate near-term revenue. “Buyers” often acquire these assets through M&A, and it serves as a fast-track path to get into a specific disease area or therapeutic modality. However, there are still significant, and sometimes unexpected clinical and commercial risks with later-stage assets.

For example, Gilead has been one of the most active M&A buyers in the past few years. They have the best-in-class HCV franchise that “works too well to cure all reachable patients”, and thus its blockbuster status only lasts for 4 years. Their current major revenue source, the HIV franchise, already has some patent expirations in 2021, and the major patent cliff will be in 2025. Gilead looks to get into oncology after Daniel O’Day became the CEO in 2018. They made a few M&As to get some promising assets in oncology, but many of them have unexpected setbacks. Anti-CD19 CAR-T therapy from the Kite Pharma acquisition is a revolutionary drug for last-line patients with B-cell malignancies, but its sales number in 2021 is less than $1B (considering that Gilead paid ~$12B to acquire Kite). Anti-TROP2 ADC Trodelvy from the 2020 $21B acquisition of Immunemedics improves the PFS of last-line HR+/HER2- metastatic breast cancer patients by just 1.5 months, which leaves some question marks on whether it has potential blockbuster potential. Anti-CD47 antibody Magrolimab from the 2020 $4.8B acquisition of Forty-Seven has toxicity concerns as its pivotal trial in AML and MDS was put on clinical hold by FDA earlier this year.

(4) Extend the existing life of blockbuster drug

Extending the life cycle of the existing blockbuster drug is another attractive way to generate more revenues before the patent cliff. We haven’t read much into the life cycle management of commercial drugs, but we will use Humira, Abbvie’s anti-TNF antibody that named the best-selling drug for many years and generated >$200B in sales in the past two decades, as an example to illustrate some common strategies

New indications: Humira was initially approved by the FDA to treat rheumatoid arthritis in 2002. In the next 20 years, more than 700 clinical trials have been conducted using Humira, and now it has been approved for 9 autoimmune indications. The most recent label in ulcerative colitis was approved just in 2021. Indication expansion enables continuous market expansion of the blockbuster drug, and technically each new indication (method of use patent) starts a new market exclusivity clock.

Patents: The (in)famous patent portfolio around Humira has quite some media spotlights in the past (eg. This 2017 Bloomberg Article, and This 2020 Endpoint News Article). The continuously growing list of patents around Humira, especially on new formations, aims to discourage or at least delay biosimilar competitors to get into the market.

Litigations: with a sophisticated patent portfolio in hand, Abbvie has attempted a number of litigations against whoever plans to make a Humira biosimilar, including Alvotech, Boehringer Ingelheim, Coherus, Pfizer, Amgen, Mylan, Samsung Bioepis, Sandoz, Fresenius Kabi, and Momenta… All of them eventually negotiated a settlement with Abbvie to somehow delay the launch of the Humira biosimilar, as the first launch will not be sooner than 2023.

How did biotech survive the blockbuster dilemma?

Getting through the blockbuster dilemma, there are two paths for commercial-stage biotech companies: remain independent and get more blockbuster drugs in line, or get acquired by pharma. Choosing either path involves complicated strategic decision-making of company management and alignment of stakeholder interests.

For companies seeking to remain independent, getting more blockbuster drugs is necessary. Earlier we talked about Regeneron’s success to get Dupixent and REGN-COV just a few years after its first blockbuster Eylea. Amgen is another example of biotech remaining independent after the initial blockbuster dilemma. After their first blockbuster drug Epogen (recombinant EPO) hit the market in 1989, Amgen quickly got another blockbuster drug Neupogen (recombinant G-CSF) in 1991. The reformulated long-lasting versions of Epogen and Neupogen got approved in early 2000 and continued to be a big commercial success. They also acquired new blockbusters through acquiring later-stage assets, obtaining Enbrel (another anti-TNF antibody) from the Immunex acquisition. More recently, Amgen developed a KRAS-G12C inhibitor adagrasib that also has big potential in oncology, and acquired ChemoCentryx earlier this year to obtain TAVNEOS (complement C5a inhibitor) for the broad autoimmune disease market.

Companies at the edge of the blockbuster patent cliff but unlikely to have future blockbusters are susceptible to being acquired by big pharma. Celgene’s major blockbuster drug Revlimid (a molecular glue to treat multiple hematopoietic malignancies), generating ~$13B sales in 2021, is facing a patent cliff in 2022. Two other major drugs. What’s worse, their other top-selling drugs, Pomalyst and Abraxane, also have a 2022 patent expiration date. Although Celgene acquired Kite to get in the CAR-T game early, that’s too little to fix the nearly $20B hole after 2022. As a result, Celgene got acquired by BMS in 2019.

What about the future?

During our research, we found a very interesting company that might face a blockbuster dilemma soon: Moderna. We all know the success story of the mRNA COVID vaccine that saves the world. Moderna has generated $18.5B in revenue from the COVID mRNA vaccine in 2021 alone. They have nearly $20B cash on hand. But the demand for the COVID vaccine is rapidly declining. What would Moderna do to handle this shortest-ever blockbuster dilemma? Would people take an annual seasonal flu + COVID combo vaccine? What about the blockbuster potential of future infectious disease mRNA vaccines, or whatever drug candidate coming out from “Moderna Genomics”? (BioNTech could face the same problem)

How would Gilead, Vertex, Abbvie, and many other companies handle their versions of the blockbuster dilemma in the next few years?

With the new prescription drug legislation signed into law recently that mandates drug price discounts after 9 years (for small molecule drugs) or 13 years (for biologics), how would that change the pharma industry dynamic?

The biotech industry is driven by innovation. For now, the blockbuster dilemma incentivizes or even forces biotechs and pharma to chase the next blockbuster drugs. This is a blessing for us passionate about biotech innovation, and ultimately for patients.

About the authors

I’m Liang, a final year PhD student at the Broad Institute & Harvard Medical School I work on new functional genomic technologies to find cancer therapeutic targets and mechanisms (here’s my first-author Cancer Cell perspective article on targeting pan-essential genes). I just finished a fellowship at Flagship in summer 2022, and worked at Harvard OTD for 2 years as a senior business development fellow. I’m passionate to start a career at the intersection of science and business for new therapeutics. Contact me: Twitter, Linkedin

I’m Kirill, a pathology resident at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, and Harvard Medical School. I am passionate about how new diagnostic modalities are reshaping the way medicine is practiced. Between medical school and residency, I have been involved in multiple healthcare startups, where I helped build and ship products in the rare disease space and precision medicine (January.ai, Asimov Medical). Contact me: Twitter, Linkedin