Deep-dive into platform biotech companies: phenotypes, business models, destinations...

We studied over 30 platform companies and share what we have learned. Moderna, Alnylam, Intellia, Recursion, Ginkgo, Kite, Genentech...

Biodraft_ is a biotech blog started by Liang Chang (PhD student at Broad/Harvard) and Kirill Karlin, MD (pathology resident at BIDMC/HMS). As trainees in science/medicine and students in biotech, we post our monthly biotech study notes here, which are mostly deep-dive analyses of interesting biotech areas we recently learned. Click here for an introduction article about Biodraft, Liang, and Kirill.

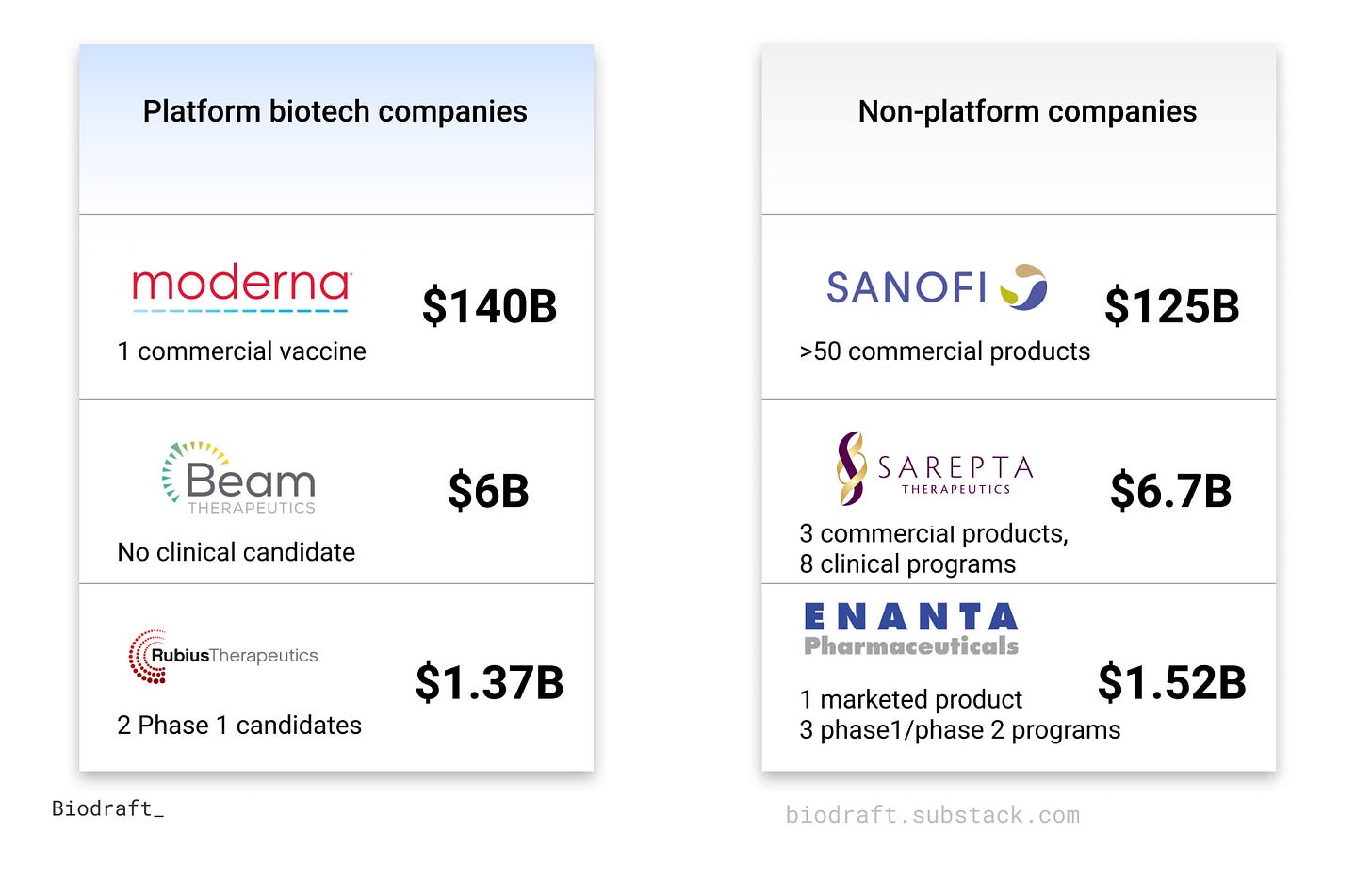

Platform biotech companies have recently drawn significant attention in Kendall Square and across Wall Street and main streets. During the COVID19 pandemic, Moderna and BioNTech are prime examples to demonstrate the efficiency and adaptability of the mRNA platform, developing two highly effective COVID vaccines in just one year. Moderna’s market cap peaked at >$200 billion in August 2021, 30x its pre-COVID level, and even briefly surpassed many Pharma giants, including Merck, Novartis, and Sanofi. This success story promises hope that platform biotech companies can accelerate solving many other human health challenges. On this other hand, the skyrocketed valuations of platform biotech companies in both private and public stages, often with early and non-yet-derisked assets, raised some concerns about potential bubbles in this space: As an example, Beam Therapeutics @$6B market cap with no IND yet vs. Jazz Pharmaceuticals @8B market cap with six marketed drugs.

What are platform biotech companies and their business models? What are some of the critical strategic decisions in these companies’ lifecycles? What are the outcomes if things go well, or not well? How do investors deal with the valuation dilemma around platform biotech companies? After studying over 30 platform companies, we take a stab to answer these questions in this deep-dive article.

What are platform biotech companies?

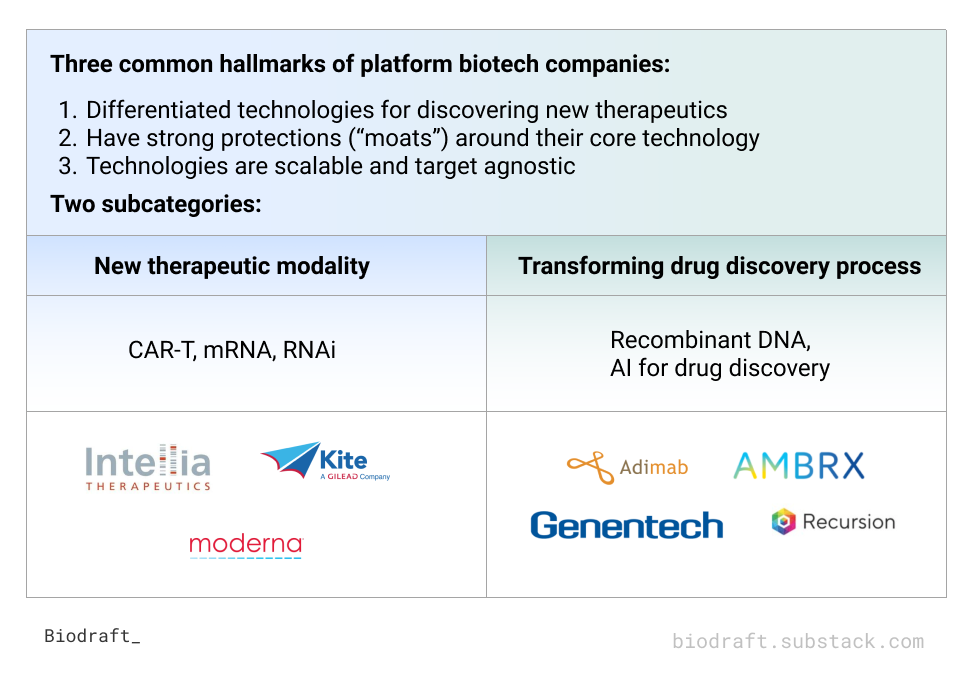

We identified three shared features and two distinct classes of platform biotech companies in the table below:

Common features:

They have differentiated technologies for discovering new therapeutics

The first part, “A differentiated technology”, is typically the starting point for a platform company. The technology can be a fundamental science discovery that changes our understanding of biology (such as RNAi and CRISPR-Cas9) or engineering inventions that expand our toolbox to understand and intervene with human disease (such as CAR-T and recombinant DNA technologies). Many of these technologies initially come from academic labs through years of dedication in a specialized field. More recently, there have been many efforts to systematically streamline the “technology invention → platform company formation” process through either the labs of entrepreneurial PIs (e.g., George Church, Bob Langer) or venture-creation-focused VCs like Third Rock Ventures or Flagship Pioneering.

Our analysis is focused on platform biotech companies around therapeutics development. Many other platform companies are working on other sectors, including synthetic biology (e.g., Ginkgo, Zymergen), life science tools (e.g., Illumina, 10x genomics), and beyond. Since the business models and strategies in non-therapeutic sectors differ, each category might be worth a separate deep dive.

They have strong protections (“moats”) around their core technology

Strong IP around the core technology is a critical comparative advantage for platform companies. Exclusive IP licensing from academic institutions is a good start, and the continuous effort to broaden the IP portfolio by internal R&D and collaborations is also very important. A good example is in the CRISPR field, where the exclusive licenses for Cas9 human therapeutics applications were assigned to Caribou (Berkeley/Doudna), Editas (Broad/Zhang), and CRISPR Therapeutics (Vienna/Charpentier). Pretty much every company intending to use Cas9 needs to talk to them and get sub-licensing or collaborations.

In addition to IP, moats for platform biotech companies can be established in several other ways. For academic spin-offs, the PIs who invented the technology often contributed scientific expertise and know-how as the companies’ scientific co-founders and/or scientific advisory board members. For technologies that are hard to patent, such as AI algorithms for drug discovery, securing large-scale high-quality datasets is a crucial comparative advantage to train and refine the algorithm. For therapeutic modalities in which manufacturing at scale is a major challenge, such as AAV vectors and antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs), strategic decisions to invest in manufacturing plants and strong CMC expertise can serve as an additional layer of differentiation.

Their technologies are scalable and target agnostic

The true power of platform biotech companies is that they can be scalable. Once the technology platform is proven to work for one indication, it is likely to be rapidly expandable to tackle a whole class of indications. For example, mRNA technology for vaccine development against infectious diseases caused by viruses after the success in COVID, and GalNac-conjugated RNAi for treating genetic diseases in the liver. However, finding the biological problem that is most suitable for a platform technology to solve, aka “technology-indication fit”, is not a trivial problem. As we will discuss in a later section, many companies need to pivot from their initial attempt.

Two classes

New therapeutic modality

A major class of platform companies works on a new modality for treating human diseases. They can be either based on brand new biological findings (e.g., RNAi, CRISPR) or engineering innovations (e.g., chemical modifications around mRNA, LNP, CAR-T, PROTAC). Many of these technologies have successfully completed clinical proof-of-concept in the past 10 years, extending the therapeutic modality dimension from small molecules and recombinant proteins to many additional possibilities.

Transforming a specific step in the therapeutic development lifecycle

These platform companies work on the established drug discovery workflow, creating a solution that can potentially transform one or more steps in this process. Aurora Biosciences is one of the earliest examples in this category, working to expand the scale of high-throughput compound screen (HTS) assays for small molecule drug discovery. Vertex acquired them in 2001, and their early programs later became the foundation of Vertex’s cystitis fibrosis franchise. A few more recent examples are Ambrx (using non-natural amino acid to produce precisely-conjugated ADCs) and Adimab (yeast cell-based expression platform for mAb discovery and optimization). What’s also worth noting is the class of AI-based drug discovery companies such as Recursion and Atomwise. Like many companies in this space promise, it will take time to see whether AI will disrupt the current drug discovery process.

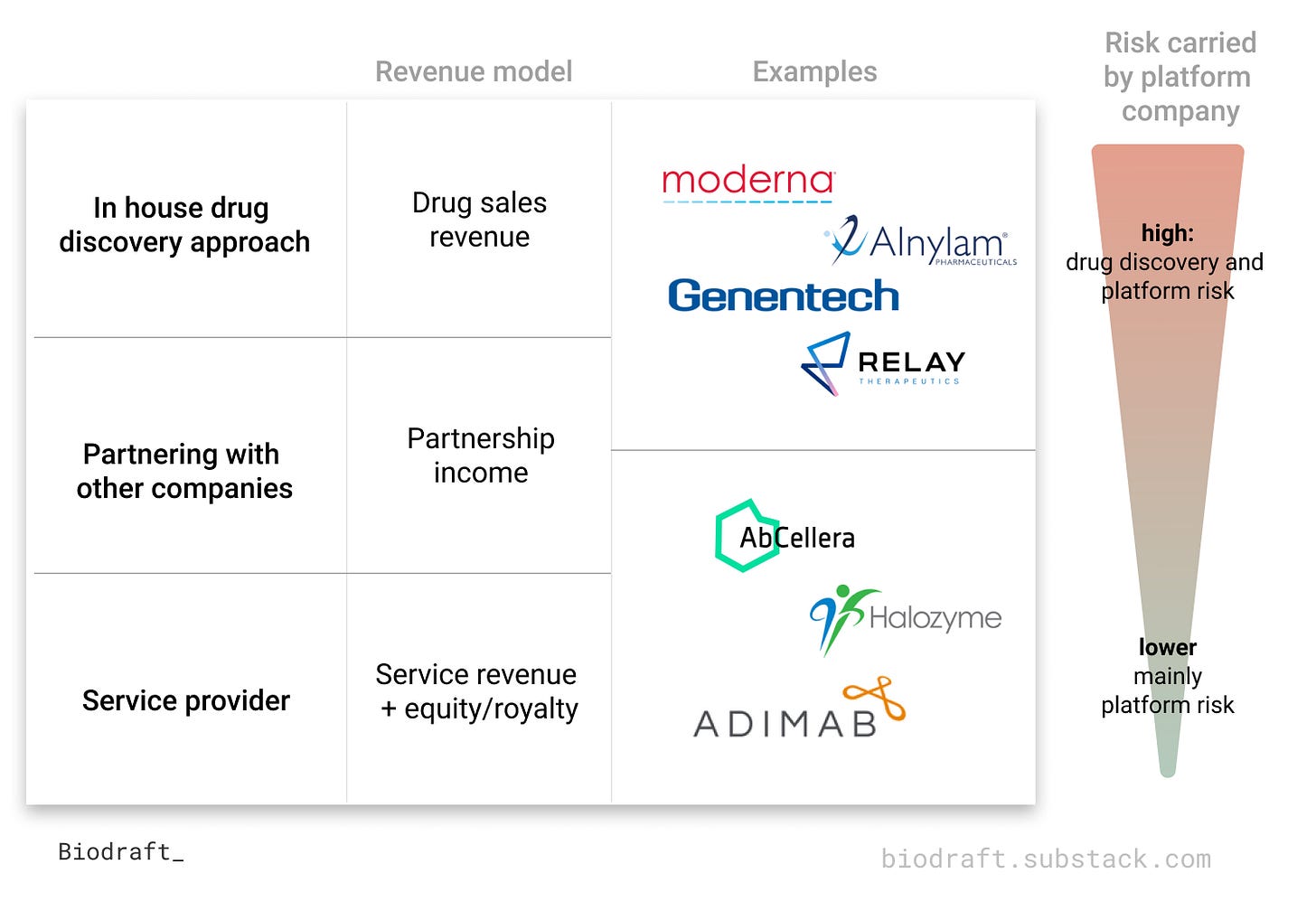

Business model decision: how do platform companies generate revenues?

There are mainly three ways to generate revenue in the therapeutic space: (1) drug revenue income, (2) partnership income, and (3) service fee income. Here’s a table summarizing the key features of each approach.

In house drug discovery approach → drug sales revenue

Companies can develop drugs in-house, push to approval, and market the drug independently. This is a high-risk, high-reward business model. Adding a billion-dollar sale/year franchise to the company’s income statement is every CEO’s dream, but getting a drug working in patients and prescribed by physicians is extremely difficult.

Several important value inflection points are along the way for the in-house drug discovery route. Pre-clinical proof-of-concept (POC), marked by a successful IND filing, is often the first value inflection point to show that the platform is capable of generating a clinical drug candidate and shows the execution ability of the leadership team to coordinate multiple lines of resources to deliver the promise. Clinical POC, marked by promising data from a phase 1 or phase 1/2 trial show that the drug candidate is safe, has decent drug-like properties, and sometimes has early efficacy signals (especially in oncology and rare disease). Pivotal trial success, demonstrating the clinical benefit of the drug candidate, is often the most important value inflection point to celebrate passing the “death-valley” of drug development. There are still some additional risks after this point, such as regulatory approval, reimbursement, and marketing risks, it’s already quite a journey and accomplishment for a platform company if they can achieve this far.

During the journey of drug discovery, the drug candidate can fail because either the platform doesn’t (platform risk), or because the therapeutic target/biological mechanism doesn’t work (biology risk). Some companies decided to take a safer route, starting with well-established drug targets to solely derisk the platform first. For example, most of the fronter-runners in the allogenic CAR-T space (Allogene, Caribou, Celyad, Precision Biosciences, to name a few) have prioritized CD-19 and BCMA, the targets which several marketed autologous CAR-T products have de-risked. Genentech, one of the earliest platform companies at its perception, chose a careful strategy to first produce the 15-amino acid somatostatin and then recombinant insulin to derisk their recombinant DNA platform in a step-wise way. Other companies took bolder moves to take both biological risk and platform risk simultaneously, working on novel drug targets or indications that have not been validated yet. Moderna and BioNTech have taken this approach on COVID mRNA vaccine and rewarded by taking the risk, whereas other vaccine developers such as CureVac (mRNA) and Inovio (DNA) didn’t achieve happy endings on the COVID front.

Pros:

Very high upside if drug works

Easier to prove the platform value (What’s better than actually having a successful drug out from the platform?)

Better to get an understandable value perception, especially in the public market (it’s easier for analysts to use a risk-adjusted DCF model for specific pipelines to valuate the company, but the “platform value” without a pipeline is hard to model)

Cons:

High cost of running drug discovery pipelines, especially in the clinical phase

Multiple layers of risk: platform risk, clinical risk, regulatory risk, market risk…

Partnering with other companies → partnership income

Platform companies, especially in their early days, usually partner with bigger biotech and pharma companies to get some early-term revenue. The partnership deals usually have three components: upfront payment (a lump sum of cash at the start of the deal), milestone payment (conditional cash payment if certain positive events happen, such as clinical trial success and FDA approval), and sales royalty (% of future revenue stream).

From our analysis, there are two major classes of the partnership deal, platform-centric collaborations, and asset-centric collaborations. We will use Alnylam as a case study to illustrate these different deals.

Platform-centric collaborations often take place at the early stage of a platform company’s life cycle, usually when the company hasn’t dived deep into its own drug candidates. These deals are typically signed with big pharma companies, more early-discovery centric, involve a small upfront cash payment and much large milestone payments. With this kind of deal, big pharma companies can use a relatively small amount of money to access a novel platform technology, and the young platform company can not only secure valuable non-dilutive funding but also gets more credibility about their technology. Below is the first collaboration deal Alnylam signed in 2003, the 2nd year after its founding, with Merck.

Asset-centric collaborations often take place when the platform company’s lead candidate already achieved preclinical or even clinical proof-of-concept. Thus, on the other side of the table, pharma or biotech companies look to collaborate with the platform company to add something new to their pipeline. These deals are usually larger in size, with higher upfront and milestone payments, and involve sales royalties. Sometimes the “buy-side” will also execute a large strategic investment in the platform company. For the platform company, they can take off some risks from clinical development, and also get a partner with much deeper clinical trial and commercialization expertise. For large pharma or biotech company, they can use their cash reserve to inject some fresh blood into their pipeline. Below is an example of asset-centric collaboration between Alnylam and Genzyme around 3 clinical candidates in 2014.

Pros

Getting income earlier in the company’s life cycle

Proving platform value through partner’s recognition

Getting complementary expertise, especially in clinical development and commercialization

Cons

Sacrificing potential upside for a promising clinical candidate

Some deals are toxic, which can push the platform company to uncomfortable situations later

Frictions around collaboration because of misalignment in priorities/expectations/working style/etc

3. Service provider → service revenue + equity/royalty

In addition to pursuing the drug candidate route (either independently or together with a partner), platform companies can also use their technology to provide service to other pharma and biotech companies. Many CRO/CDMO companies adopt this "sell shovels during a gold rush" business model to generate steady, less-risky cash flows. China-based WuXi AppTec is a remarkable success in this space, built one of the world’s largest integrated drug discovery R&D and manufacturing service companies in just 20 years, and achieved a $64B market cap. But in the CRO space where economies-of-scale matters, it takes a lot of effort for a small platform company to achieve sustainable growth. Adimab is a great example using the “CRO-like” service provider business model. They use a yeast cell-based expression platform to provide mAb discovery and optimization service, already working on >360 programs over >80 partners.

In addition to the steady cash flow, additional sales royalty payments are great sweeteners for some revenue upsides in the future. But on the other side of the table, a bigger company with a promising drug candidate in hand is obviously reluctant to share the future revenue with a small platform company. One great example is Halozyme: this San Diego-based company has successfully developed the rHuPH20 enzyme into an IV-to-SC reformulation platform technology. Their truly differentiated platform has the potential to make most of the marketed IV biologics therapeutics to a much easier subcutaneous injection. Thus, they have worked together with 11 companies that have a blockbuster biologics product, and a mid-single-digit royalty sharing is involved in nearly every deal.

Platform companies can also provide service to small startup companies, and get equity from these startup companies in return. To take one step further, they can also spin off drug discovery-focused startup companies and take a large share of equity from these spinoffs. In this way, they can use these equities to participate in the potential upside of the drug discovery business. Atomwise, an AI-based Drug Discovery company, has established 7 “portfolio companies” through their technology and joint venture.

Pros

Steady revenue early in the life cycle

Lower risk and capital requirement → less need for fundraising

Can get some upside through royalties and startup equity

Cons

Hard to maintain sustainable growth → narrower window for IPO and investor exit

Competition from other CROs, unless the technology is well-differentiated

May require sales effort early on

Where are the destinations for platform companies?

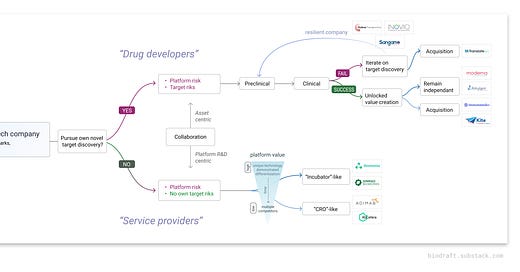

From our analysis, platform companies can be broadly categorized into two classes based on their primary business model. Drug developers devote the majority of their efforts to developing in-house drug candidates, and partner with other companies through both platform-centric and asset-centric collaborations. Service providers mainly provide platform services to other companies for cash payments, as well as royalties (from big companies) and equities (from small startup companies). They also engage with other companies through platform-centric R&D partnerships.

Companies even with a similar class of platform technologies can choose to commit to either route based on strategic decisions. For example, in the AI/computational drug discovery space, companies like Relay, Recursion, Insitro, and Valo focused on pushing their internal pipeline forward. Relay is the front runner in this space, using their protein-motion-based computational method to develop inhibitors against oncology targets previously hard to achieve target selectivity, such as FGFR2 and PIK3CA. Other companies like Schrodinger, AbCellera, Atomwise, and XtalPi lean toward the service provider route, collaborate with big companies and/or spin-off new ventures.

Drug Developers

Since drug discovery is very costly and the cash-burning rate is accelerating throughout this process, platform companies pursuing this route need to secure continuous funding along the way. They often require multiple rounds of fundings from VC investors, and consequent IPO to raise money from the public market is a major milestone to achieve. IND clearance/Phase 1 initiation is historically a “sweet spot” for an IPO, but recently more and more pre-clinical staged platform companies also successfully went public. Monte Rosa Therapeutics (developing “molecular glue” compounds for targeted protein degradation), Sana Biotechnology, Century Therapeutics (both developing iPSC-derived allogenic CAR-T/CAR-NK therapies), and Omega Therapeutics (focusing on epigenetic-editing gene therapy) are among the preclinical platform companies that recently rang the bell at NASDAQ. It will be interesting to see how long will this trend continue in the upcoming post-COVID-biotech-hype and post-zero-interest-rate era.

One common feature of public platform companies is the relatively high valuation compared with other asset-centric (“traditional”) biotech companies at the same stage. A few pairs of platform vs. traditional companies market cap to illustrate this point (numbers at Oct 27 2021 market closing):

The DCF model is commonly used to estimate the value of a clinical-stage biotech company, based on the probability-adjusted future cash flow from lead drug candidates in the pipeline. However, when applying it to model platform companies, the actual market cap is often much higher than the DCFs of leading clinical candidates. So what’s the right way to model and estimate the “platform values” beyond the drug candidates in the pipeline? Is high-valuation a hype or justifiable feature for platform biotech companies (since Tesla has reached a $1T market cap anyway)?

As the drug candidate becomes less risky and more valuable after rounds of positive data in animals and patients, it also becomes more attractive to buyers. Acquisition by pharma is one possible destination of “drug developer” platform companies. If the acquisition takes place after some positive clinical data, the purchase price is often at a premium. Gilead’s $11.9B acquisition of Kite Pharma and $21B acquisition of Immunomedics, and Bayer’s $2B acquisition of AskBio are among the recent “happy ending acquisitions” of platform companies. Platform companies can also be bought at a discount when the pipeline doesn’t roll out well but the platform is still attractive. For example, Sanofi bought Translate Bio to get its mRNA technology platform right after Translate Bio’s Phase1/2 trial in cystic fibrosis failed. If the platform company carries through its drug candidate until FDA approval, they can become commercial-stage biotech companies. This is a great place to be in since they have clearly demonstrated the power of their platform technology, expect considerable revenues coming soon, and also likely have an innovative pipeline from their platform technology to give investors confidence for future sustainable growth. Often from platform to therapy is a long and hard journey -Genentech takes 9 years to get there, Alnylam takes 15 years, and Moderna takes 7 years. On the other hand, many companies failed at their first try in drug discovery, but use their platforms to reiterate this process with a new drug candidate, and sometimes even pivot to a very different direction. These resilient platform companies include Rubius (PKU -> cancer cell therapy), Sangamo (diabetic neuropathy -> HIV -> MPS II -> hemophilia A), and Inovio (cancer -> Zika -> Ebola -> COVID).

Service providers

The business model of service provider companies makes them typically less demanding for cash early in the lifecycle: not directly working on drug discovery effectively controls the cash burn rate, and service/collaboration income from the platform in the early days can be used to support continuing R&D efforts. Thus, these companies don’t need to get in a constant rush for more venture dollars, and they can stay in private for longer if they prefer to. Also, the future growth story of a niche service provider is hard to convey in the public market, and thus might hinder the valuation of these companies if they want to pursue the IPO route. Companies that did go public in this space either provide integrated drug discovery service (AI-based small molecule/antibody discovery: Schrodinger, AbCellera, Absci) or provide a truly differentiated technology that adds value to other big pharma (sub-Q reformulation of biologics, Halozyme). The recent $1.6B Ginkgo Bioworks SPAC is also an interesting example that the service provider business model in the synthetic biology field can be accepted by public market investors.

The service provider platform companies can mainly operate in the “CRO-like” model by offering platform service for cash or royalty income. Adimab, Halozyme, AbCellera, and XtalPi are among the companies in this category. To thrive in the CRO market, companies usually aim to provide an integrated drug discovery/development workflow with ensured compliance requirements to satisfy their big pharma customers. Other companies take the “Incubator-like” model to spend a lot of effort on incubating new startup companies. Notable examples include Atomwise and Ginkgo. Interestingly, Moderna in its early days (2014-2016) also work in this model, spun off several asset-centric companies including valera, caperna, onkaido and elpidera. It transformed into a “drug developer” we are familiar with today in 2017.

Epilogue: What’s more?

This deep-dive on platform company all started from an occasional chat between Kirill and Liang: how to get a fair platform value estimation for Moderna, Intellia, and others? Are they over-valued, and if so, by how much?

After looking into >30 platform companies and writing this whole article, we still haven’t got there to answer this question. Since platform company is such an open and exciting area in biotech, the more we read and study, the more we want to explore. Here are a few areas we hope to do more analysis to figure out, but not yet:

How to assign proper platform value to these companies?

A retrospect analysis of M&A history. How many platform-centric purchases delivered the promise?

A few case studies on up and downs (Moderna, Alnylam)?

If you’re interested in any of these areas, or have some new questions about platform technology, please send us a note! We would like to have some more brainstorming, and maybe a follow-up article. Let us know, and see you next time!

About the authors

I’m Liang, a 5th year PhD student at the Broad Institute and Harvard Medical School I work on new functional genomic technologies to find cancer therapeutic targets and mechanisms (here’s my first-author Cancer Cell perspective article on targeting pan-essential genes). I’m also a senior business development at Harvard OTD, helping to commercialize early life science technologies right out of Harvard labs. I’m excited about learning the science and business around new therapeutics, from lab to patients. Contact me: Twitter, Linkedin

I’m Kirill, a pathology resident at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, and Harvard Medical School. I am passionate about how new diagnostic modalities are reshaping the way medicine is practiced. Between medical school and residency, I have been involved in multiple healthcare startups, where I helped build and ship products in the rare disease space and precision medicine (January.ai, Asimov Medical). Contact me: Twitter, Linkedin

Thanks, interesting post, but Schrodinger and Abcellear have pipelines, so they are not "just" service companies, certainly. Also, Cyclica was acquired a couple years ago by Recursion.

https://www.baybridgebio.com/blog/platform-underperform.html